Volumetric Photon Mapping Project

In computer graphics, caustics refer to patterns of light formed when light rays focus onto specific areas of a surface, often through specular reflections or refractions. When such light rays transmit through a participating medium, they can be scattered and result in volume caustics. In real life, caustics can commonly be observed under a wavy water surface or in the shadow of a curved glass of liquid. An example of volume caustics could be the sun casting beams of light through a misty morning forest – an effect I witnessed during a visit to Sequoia National Park, which also served as the inspiration for this project.

Drawn to the astonishing visual effects of caustics and volume caustics, I decided to implement photon mapping and volumetric photon mapping, and I was fortunate to have Professor Theodore Kim supervise my project. This work builds upon the distributed ray tracer which I implemented from scratch in C++ for Professor Kim’s Computer Graphics course project.

I implemented the algorithms based on a series of publications by Dr. Henrik Wann Jensen and Dr. Per H. Christensen [1][2][3]. In the sections following the demo gallery, I will provide a brief overview of the photon mapping and volumetric photon mapping algorithms, along with some technical details about my implementation.

Gallery

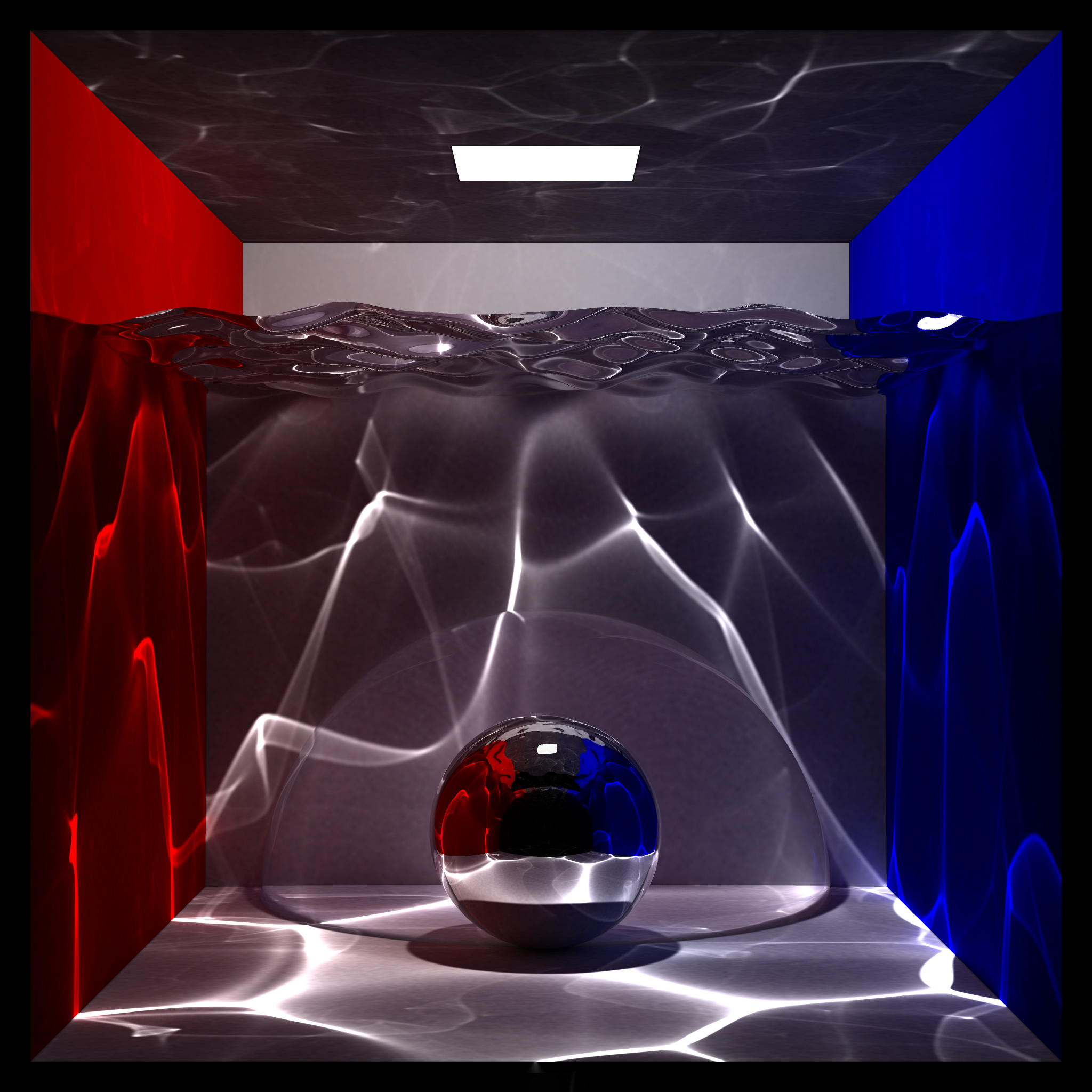

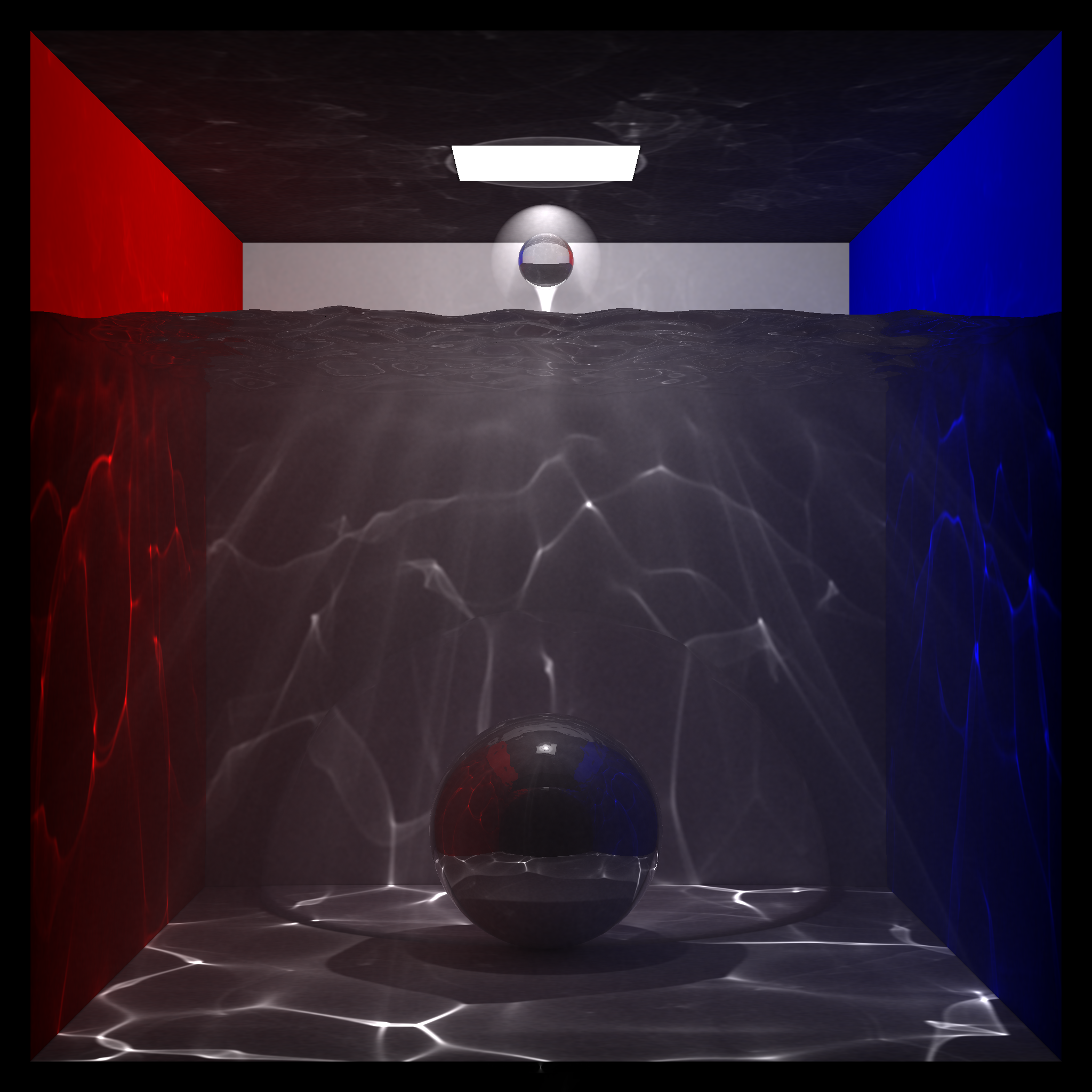

|  |

|---|---|

| Box with Water Scene 1 - Volumetric Photon Mapping | Box with Water Scene 2 - Photon Mapping |

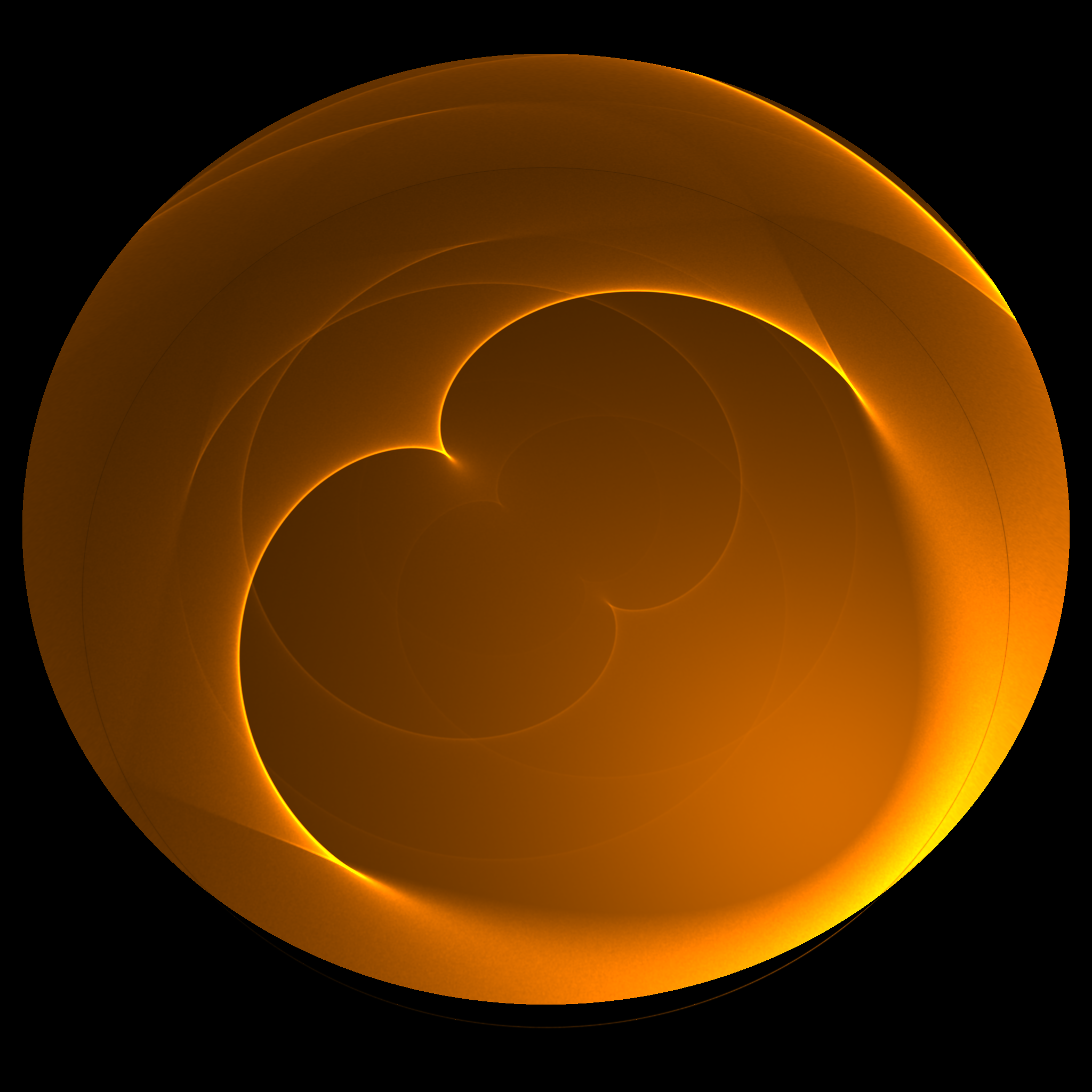

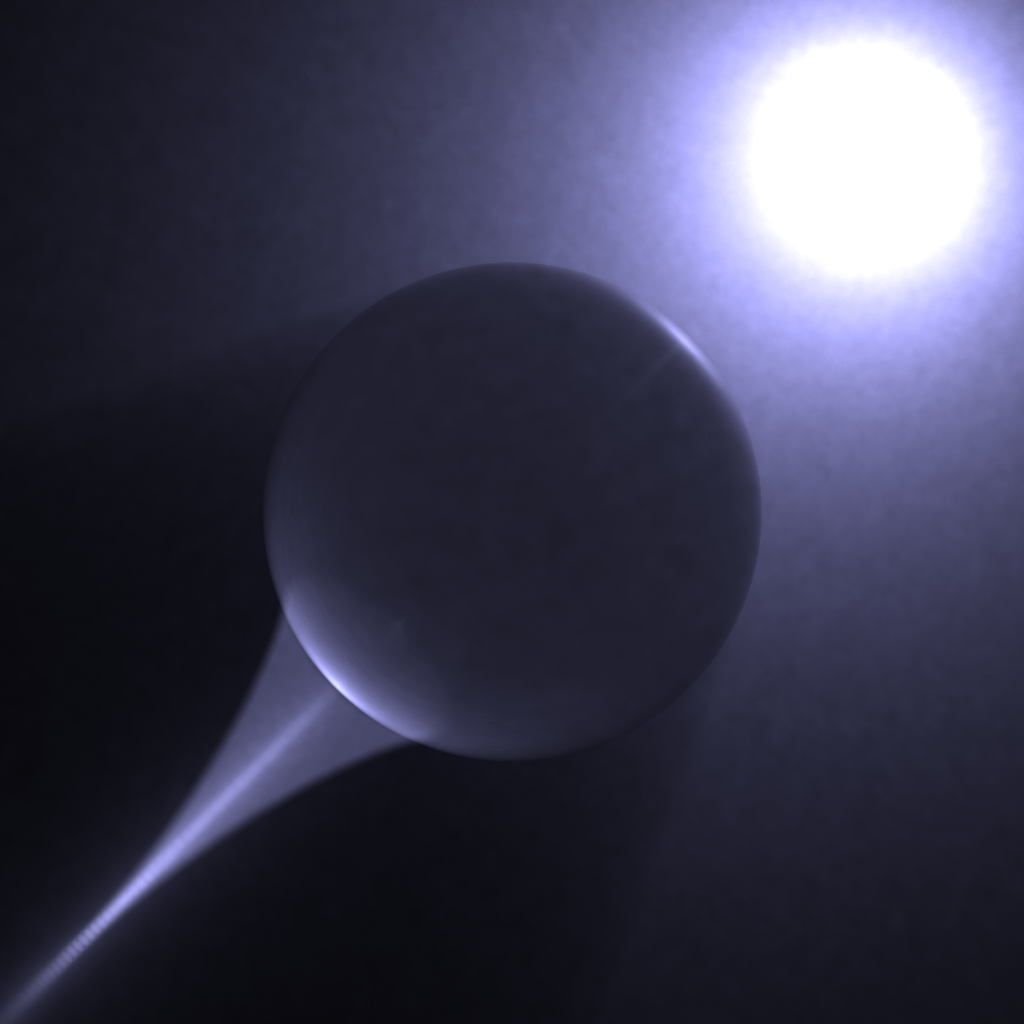

|  |

|---|---|

| Volume Caustic through a Fog Medium | Cardioid Caustic of a Reflective Ring |

Photon Mapping

The photon mapping algorithm was introduced by Dr. Henrik Wann Jensen in his 1996 paper, “Global Illumination using Photon Maps” [2]. This overview synthesizes the key concepts I have learned from his seminal paper and his comprehensive book, Realistic Image Synthesis Using Photon Mapping [1]. Additionally, I will share some details about my implementation of the algorithms and the “box with water” demo scene, and discuss the challenges I encountered during the process.

As a global illumination algorithm, photon mapping is capable of rendering indirect illumination and caustics more efficiently than pure Monte Carlo ray tracing methods. The technique can also be extended to volumetric photon mapping, which supports participating media and renders volume caustics.

The standard photon mapping algorithm consists of two passes:

1st Pass: Photon Tracing

Photon Representation

Before diving into the photon tracing process, it is important to briefly describe the fundamental element of the algorithm – the photon. In my implementation, I created aPhotonclass, where each photon instance stores its position, direction, and color (power, in RGB). The class also includes several boolean flags to track information such as wether the photon has been scattered, but I will omit the technical details for now.

It is worth noting that, by including position and direction information, each photon can effectively be treated as a ray. This allows the ray tracing algorithm to be adapted for photon tracing with only slight modifications.Photon Emission

Photon tracing is a forward ray tracing process, as opposed to backward ray tracing, which starts at the camera. In photon tracing, each photon is emitted from a light source, and its starting position and direction can be sampled based on the characteristics of the light source. For example, the starting position could be uniformly distributed across an area light source, and the starting direction could be sampled within a hemisphere or a cone. Once generated, the photon is treated as a ray and traced through the scene.

In my box-with-water demo scene, I implemented several sampling strategies. However, in the final demo, the main light source on the ceiling is modeled as a cosine-weighted hemispherical point light source to produce sharper caustics.

One additional detail is that if a light source emits \(N\) photons, then each photon should carry \(\frac{1}{N}\) of the light source’s power.Photon Scattering

When a photon hits the scene geometry (i.e. a ray intersection), it interacts with the surface and can either be reflected (diffusely or specularly), transmitted, or absorbed. The action of the photon is determined using a technique called Russian roulette, which eliminates the need to generate additional photons during the tracing process.

For example, when a photon hits a refractive surface, instead of splitting its power into a transmitting photon and a reflecting photon based on the Fresnel equations, the Russian roulette algorithm will let the photon either transmit or reflect entirely, retaining its original power.

The Russian roulette algorithm determines the photon’s action using a probability distribution derived from the interacting surface’s material parameters. For instance, when a photon interacts with a surface, the surface’s diffuse coefficient \(d\) and specular coefficient \(s\) could be used to assign probabilities: the photon can have a probability of \(d\) to be diffusely reflected, \(s\) to be specularly reflected, and \((1 - d - s)\) to be absorbed. Similarly, when a photon hits a refractive surface, the coefficients computed from the Fresnel equations (which use the refractive index of the surface material) can be used as probabilities for specular reflection and transmission, respectively.

After the photon action is determined, the photon’s properties, such as position and direction, are updated following ray tracing practices.Photon Storing

At each interaction of a photon with a non-specular surface, the information of the incoming photon is stored in the photon map – a three-dimensional data structure – at the position of interaction. This photon map is maintained independently from the scene geometry, ensuring the decoupling of illumination and geometry. The key operation for the photon map is locating the nearest neighboring photons at any given position, which is essential for the subsequent rendering pass of the photon mapping algorithm. This makes the kd-tree – a multi-dimensional generalization of the binary search tree – an ideal data structure for the photon map. During the photon tracing pass, photons are initially stored in a flattened array, which will be transformed into a kd-tree at the end of the process.

A common optimization in photon mapping is to omit storing photons at their first non-specular interaction, as direct illumination can typically be computed by the ray tracing component of the algorithm. With this approach, the photon map is used exclusively for indirect illumination, which is the strategy I adopted in my implementation.

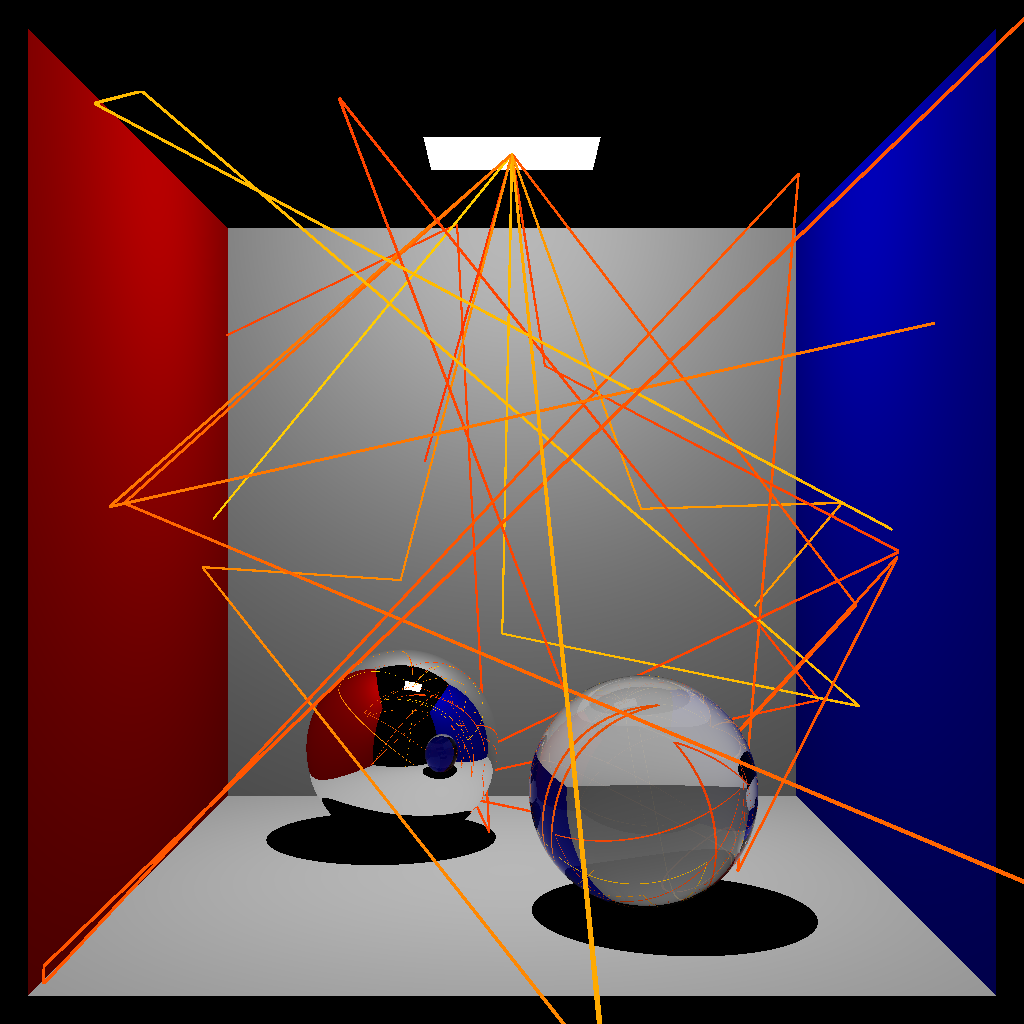

|  |

|---|---|

| Photon Tracing Visualization | Photon Storing Visualization |

2nd Pass: Rendering

Radiance Estimate

During the rendering pass, the photon map is used to compute the reflected radiance at any given point in the scene. Without participating media, these points are always on the surfaces of the scene geometry.

To estimate the reflected radiance at a specific position \(x\), the nearest \(n\) photons are retrieved by querying the photon map. The reflected radiance is then approximated using the following equation:

———————————————————————————————————— $$ L_r(x,\vec{\omega}) \approx \sum_{p=1}^n f_r(x,\vec{\omega}_p, \vec{\omega}) \frac{\Delta\Phi_p(x,\vec{\omega}_p)}{\Delta A} $$ This is Equation (7.4) of [1], where

\(L_r\) is the reflected radiance

\(f_r\) is the BRDF at \(x\)

\(p\) is a photon with power \(\Delta\Phi_p(x,\vec{\omega}_p)\)

\(\Delta A\) is the area (\(\Delta A = \pi r^2\) assuming the photons are on the same surface)

————————————————————————————————————

I will omit the detailed deriviation starting from the rendering equation in this overview. If you are interested, please refer to the source for more information.

The canonical way to perform radiance estimation is to locate the nearest \(n\) photons around \(x\) and determine the radius \(r\) based on the distance to the furthest photon (nearest neighbors search). However, I observed that with a sufficiently high photon count, radiance estimation produces better results when the search radius \(r\) is fixed to a small value, allowing \(n\) to vary with photon density (radius search). I found this approach particularly effective for rendering caustics, as it results in sharper edges.

Another technique for rendering caustics involves splitting the photon map into a global photon map and a caustics photon map, with the latter dedicated to storing photons that have undergone specular reflections or transmissions. When I tested this approach, I used the nearest neighbors search for the global photon map and the radius search for the caustics photon map. However, this method did not result in a significant improvement in caustics quality while increasing both computational and memory costs. Therefore, the demo scenes use only a global photon map and the radius search.The Cone Filter

The cone filter is a simple yet efficient technique for sharpening the rendered caustics. It assigns a weight of \(w_{pc}=(1-\frac{d_p}{kr})\) to each photon \(p\), where \(d_p\) is the distance between \(x\) and \(p\), and \(k\) is a filter constant that satisfies \(k \geq 1\) and is often taken to be \(1\).

Since the photons are assumed to be on two-dimensional surfaces, the cone filter can be normalized with \((1-\frac{2}{3k})\). After applying the cone filter, the radiance estimate equation becomes:

———————————————————————————————————— $$ L_r(x,\vec{\omega}) \approx \frac{\sum_{p=1}^n f_r(x,\vec{\omega}_p, \vec{\omega}) \Delta\Phi_p(x,\vec{\omega}_p) w_{pc}}{(1-\frac{2}{3k})\pi r^2} $$ This is Equation (7.9) of [1] and Equation (5) of [2]

————————————————————————————————————

|

|---|

| Cardioid Caustic of a Reflective Ring, Rendered using the Cone Filter |

Participating Media

Before delving into volumetric photon mapping, I will provide a brief overview of the concept of participating media in computer graphics. This summary is based on what I learned from Chapter 11 of Physically Based Rendering: From Theory to Implementation (PBRT) (4th Edition) [4].

Participating media refer to regions filled with small particles that interact with light as it travels through the medium. Fog and cloudy water are common real-world examples of participating media. Due to the massive number of particles present in such media, it is infeasible to model each particle individually. Instead, when rendering a scene with participating media, the media’s effects on light are modeled probabilistically.

Physical Processes in Participating Media

These are three major physical processes that influence light transport in participating media. I will quote their definitions from PBRT [4]:

- Absorption: the reduction in radiance due to the conversion of light to another form of energy, such as heat.

- Emission: radiance that is added to the environment from luminous particles.

- Scattering: radiance heading in one direction that is scattered to other directions due to collisions with particles.

In my implementation of participating media, I made the simplifying assumptions that all media are non-emissive and homogeneous – meaning the properties of a medium are constant throughout its region.

Coefficients and Transmittance

Absorption, Scattering, and Extinction Coefficients

The absorption coefficient \((\sigma_a)\) of a medium represents the probability per unit distance that a light ray traveling through the medium will be absorbed upon hitting a particle.

Similarly, the scattering coefficient \((\sigma_s)\) represents the probability per unit distance that a light ray traveling through the medium will hit a particle and scatter towards a different direction (out scattering).

Both of these interactions reduce the ray’s radiance. Thus, the sum of \(\sigma_a\) and \(\sigma_s\) is known as the extinction / attenuation coefficient, denoted as \(\sigma_t\).

Another important quantity is the ratio of the scattering coefficient to the extinction coefficient \((\frac{\sigma_s}{\sigma_t})\). This value is called the scattering albedo, and it will play a key role in the Russian roulette process for volumetric photon mapping, which will be introduced in the next section.Transmittance and Beer’s Law

For any single light ray, the events of scattering or absorption intuitively either occur or not. However, in participating media, these interactions are modeled as continuous reduction in radiance, which statistically achieves the same overall effect.

The fraction of radiance that remains as a light ray travels from point \(p\) to \(p'\) is represented by the transmittance \(T_r(p \rightarrow p')\).

Under the homogeneous medium assumption, the transmittance from \(p\) to \(p'\) can be easily computed following Beer’s Law:

———————————————————————————————————— $$ T_r(p \rightarrow p’) = e^{-\sigma_t d} $$ This is Equation (11.7) of [4], where

\(d\) is the distance between \(p\) and \(p'\)

\(\tau(p \rightarrow p') = \sigma_t d\) is also known as the optical depth

————————————————————————————————————

Phase Function

The phase function for participating media is analogous to the BSDF for surfaces – it describes the distribution of outgoing directions \((\omega_o)\) given the incident direction \((\omega_i)\) in a scattering event. In my implementation, I assume that all participating media are isotropic, meaning the distribution of scattering directions is rotationally symmetric. In this case, the phase function depends only on the angle \(\theta\) between \(\omega_i\) and \(\omega_o\).

I will discuss the specific phase function I used – the Henyey-Greenstein Phase Function – in more detail in the next section.

Implementing the Medium Framework

Prior to implementing participating media and volumetric photon mapping, I first needed to create a Medium class and a framework that allows rays and photons to track their current medium.

The Medium class I developed includes a ScatteringCoefs struct to store \(\sigma_s\), \(\sigma_a\), \(\sigma_t\), and the scattering albedo \(\frac{\sigma_s}{\sigma_t}\). The class also includes a PhaseFunction class, the medium’s refractive index, and several boolean variables to track properties such as whether the medium requires ray marching. Certain media like air or glass do not “participate” in the light transport process beyond their surfaces and thus do not require ray marching. I will describe the ray marching process in the next section.

To enable rays/photons to track the medium they are currently in, I implemented a medium stack for each ray/photon, initialized with its initial medium. When a ray/photon enters a new medium, the new medium is pushed onto the stack; when it exits the current medium, it is popped off the stack.

Each primitive in the scene, whether a closed geometry (e.g., a sphere) or an open one (e.g., a triangle), is assigned a Medium corresponding to the medium it “surrounds,” which is the medium on the side opposite to its normal. When a ray/photon intersects a primitive, if it hits the side aligned with the normal, it is entering a new medium; otherwise, it is exiting the current medium.

An issue I encountered was the “leaking” of rays/photons at medium boundaries. Due to floating-point precision errors, rays/photons could, in extreme cases, cross a medium boundary unexpectedly – possibly between the edges of two triangles that are supposed to be perfectly-sealed. This issue is less likely to occur when the medium is enclosed by a single, closed surface (such as a sphere). However, in the box-with-water scene, the water surface is composed of approximately six million triangles.

To address this problem, I implemented additional checks during medium stack operations. For example, when a ray/photon intersects a primitive and exits a medium, it verifies whether the primitive’s medium matches its current medium. If a mismatch occurs, the tracing process for that photon/ray is terminated. Due to the rarity of leaking events, discarding a single photon/ray has no noticeable impact on the overall render.

|

|---|

| The Box with Water Scene after Implementing the Medium Framework (Before Volumetric Photon Mapping) |

| The scene features a glass dome submerged underwater, with a reflective sphere positioned half inside and half outside the glass dome. |

Volumetric Photon Mapping

The photon mapping algorithm was extended to handle participating media by Dr. Henrik Wann Jensen and Dr. Per H. Christensen in their 1998 paper, “Efficient Simulation of Light Transport in Scenes with Participating Media using Photon Maps” [3]. While the term volumetric photon mapping was not coined in this paper, I have adopted it from the 2008 paper, “The Beam Radiance Estimate for Volumetric Photon Mapping,” by Dr. Wojciech Jarosz, Dr. Matthias Zwicker, and Dr. Henrik Wann Jensen [5]. The following overview summarizes what I learned from the 1998 seminal paper [3] and Chapter 10 of the book [1].

1st Pass: Photon Tracing

In a scene with participating media, photon tracing must account for the effects of the physical processes on photons. Specifically, as a photon travels through a participating medium, it may be scattered or absorbed. I refer to such an occurrence as an “interaction event”.

The average distance for such an interaction to occur depends on the extinction coefficient of the medium: \(d = \frac{1}{\sigma_t}\) (Eq 10.21 of [1]). Applying importance sampling, the interaction distance can be sampled as \(d = \frac{-log(\xi)}{\sigma_t}\), where \(\xi\) is a uniform random variable in \([0, 1]\) (Eq 10.22 of [1]).

In my implementation, for a photon traveling through a participating medium, the distance to the boundary of the current medium (\(d_{total}\)) is computed via ray intersection. The interaction distance \(d\) is then sampled. If \(d<d_{total}\), an interaction event occurs within the participating medium is handled accordingly. Otherwise, the photon exits the medium as usual. Since this process models a single photon, no power scaling is required.

Photon Scattering

If an interaction event occurs, the type of interaction is again determined using Russian roulette. Recall that the scattering albedo of the medium represents the ratio of the scattering coefficient to the extinction coefficient: \(\Lambda = \frac{\sigma_s}{\sigma_t}\). Accordingly, the probabilities used in the Russian roulette process should be \(\Lambda\) for scattering and \((1-\Lambda)\) for absorption.

In the case of a scattering event, the photon’s new direction is sampled from the phase function. The phase function that I implemented is the Henyey-Greenstein Phase Function approximated by the Schlick Phase Function:

————————————————————————————————————

The Henyey-Greenstein Phase Function: $$ p(\theta)=\frac{1-g^2}{4\pi(1+g^2-2g\cos\theta)^{1.5}} $$ Importance Sampling: $$ \cos\theta=\frac{1}{2g}(1+g^2-(\frac{1-g^2}{1-g+2g\xi})^2) $$ These are Equations (10.12) and (10.14) of [1], where

\(\theta\) is the angle between \(\omega_i\) and \(\omega_o\)

\(g\in[-1,1]\) is the asymmetry parameter: \(g > 0\) results in forward scattering, \(g < 0\) results in backward scattering, \(g = 0\) results in isotropic scattering where the outgoing direction is uniformly distributed and independent of the incident direction

\(\xi\) is a uniform random variable in \([0, 1]\)

————————————————————————————————————

Since the Henyey-Greenstein Phase Function is roughly ellipsoidal in shape, the Schlick Phase Function could be used as a approximation that is more efficient to evaluate:

————————————————————————————————————

The Schlick Phase Function: $$ p(\theta)=\frac{1-k^2}{4\pi(1+k\cos\theta)^2} $$ Importance Sampling: $$ \cos\theta=\frac{2\xi+k-1}{2k\xi-k+1} $$ These are Equations (10.15) and (10.16) of [1], where

\(\theta\) is the angle between \(\omega_i\) and \(\omega_o\)

\(k\in[-1,1]\) is the asymmetry parameter, similar to \(g\) in the Henyey-Greenstein Phase Function

\(\xi\) is a uniform random variable in \([0, 1]\)

————————————————————————————————————Photon Storing

At the position of each interaction event – whether scattering or absorption – the photon’s information is stored in the volume photon map, which is distinct from the global photon map used for surfaces. This separation is necessary because the radiance estimation technique for participating media differ from the one used for surfaces.

It is also a common practice to omit storing the first scattering of photons, as they contribute to the direct illumination component which can be relatively easily evaluated. However, in my implementation, I still decided to store the first scattering of the photons. This approach simplifies evaluations during the ray marching algorithm, which I will discuss in the next section.

2nd Pass: Rendering

For participating media, the indirect illumination component is the gain of radiance due to in scattering – light scattered into the ray’s direction from other directions. This component is essential for producing effects such as volume caustics. Since I decided to store the first scattering of the photons, the radiance estimates will account for the in-scattered radiance from both direct single scattering and indirect multiple scattering.

Ray Marching

Before explaining the volume radiance estimate for in-scattered radiance, I will first introduce the technique of ray marching, a numerical integration method for computing the volume rendering equation. This approach divides a ray traveling through a participating medium into small segments and iteratively evaluates the radiance after each segment. The calculation accounts for direct in-scattered illumination from light sources, indirect in-scattered illumination, and attenuation of the radiance from the previous segment.

Below is a high-level formulation of the ray marching algorithm:

————————————————————————————————————

\(L_{n+1}(x,\vec{\omega})=\sum_l^N (\) direct in-scattered illumination from each light source \()\)

\(+ (\) indirect in-scattered illumination \()\)

\(+ e^{-\sigma_t(x)\Delta x} L_n(x + \vec\omega\Delta x, \vec\omega)\)

This is a high-level summary of Equation (10.19) of [1], where

\(N\) is the number of light sources

\(\Delta x\) is the step size

\(L_{n+1}\) is the radiance after the current step

\(L_n\) is the radiance before the current step

The attenuation \(e^{-\sigma_t(x)\Delta x}\) is calculated from Beer’s Law.

The details of evaluating each term using the volume radiance estimate will be explained shortly.

————————————————————————————————————Volume Radiance Estimate

To estimate the in-scattered radiance at a specific point in participating media, the previous estimation formula for surfaces is no longer applicable. Some modifications are required for it to work with media and volumes. In particular, the phase function should replace the BSDF, and the volume \(\Delta V = \frac{4}{3}\pi r^3\) should replace the area \(\Delta A\):

———————————————————————————————————— $$ (\vec{\omega} \cdot \nabla)L(x,\vec{\omega}) \approx \sum_{p=1}^n p(x,\vec{\omega}_p, \vec{\omega}) \frac{\Delta\Phi_p(x,\vec{\omega}_p)}{\frac{4}{3}\pi r^3} $$ This is Equation (10.28) of [1] and Equation (6) of [3], where

\((\vec{\omega} \cdot \nabla)L(x,\vec{\omega})\) is the increase in radiance due to in scattering in the direction \(\vec{\omega}\)

\(p(x,\vec{\omega}_p, \vec{\omega})\) is the phase function

\(p\) is a photon with power \(\Delta\Phi_p(x,\vec{\omega}_p)\)

\(r\) is the radius

————————————————————————————————————

The canonical method for computing the estimate is similar to the surface version: first, locate the \(n\) nearest photons to the position and use the distance to the furthest photon as the radius \(r\). However, I again found that by fixing the radius \(r\) and allowing \(n\) to vary with photon density, the resulting volume caustics appear sharper, particularly when the photon count is sufficiently high.Ray Marching with Volume Radiance Estimate

Using the volume radiance estimate, the terms related to in-scattered radiance in the ray marching algorithm can now be evaluated:

———————————————————————————————————— $$ L_{n+1}(x,\vec{\omega})= (\sum_{p=1}^n p(x,\vec{\omega}_p, \vec{\omega}) \frac{\Delta\Phi_p(x,\vec{\omega}_p)}{\frac{4}{3}\pi r^3})\Delta x $$ $$ +e^{-\sigma_t(x)\Delta x} L_n(x + \vec\omega\Delta x, \vec\omega) $$ This is modified from Equation (10.30) of [1], where the first two terms are combined since the volume radiance estimate accounts for both direct single scattering and indirect multiple scattering.

————————————————————————————————————

|  |

|---|---|

| Fog Scene - Volumetric Photon Mapping | Box with Water Scene - Volumetric Photon Mapping |

Additional Details

At this point, I have introduced all the core concepts and algorithms for implementing volumetric photon mapping. Below, I outline several additional technical details specific to my implementation:

Saving and Loading Photons

To avoid repeated computation when rendering the same scene (geometry and lighting) with different parameters (e.g., resolution), I implemented the option to save photons stored during the photon tracing pass to a file. This allows subsequent renders of the same scene to skip the photon tracing step by loading the saved photon data, significantly reducing computation time.

Perlin Noise Displaced Water Surface

The water surface of my box-with-water demo scene is generated by displacing the vertices of a fine rectangular grid using Perlin noise, a renowned procedural noise function introduced by Dr. Ken Perlin in 1985 [6].

I implemented a Perlin noise generator with an adjustable octave parameter, allowing for customizable levels of detail. Additionally, I incorporated the improved interpolation method introduced in Dr. Ken Perlin’s 2002 paper, “Improving noise” [7]. Instead of the “smoothstep” cubic interpolation function, \(s(t)=3t^2-2t^3\), I utilized the fifth-order “smootherstep” function, \(s(t)=6t^5-15t^4+10t^3\). This enhancement eliminates the visible grid patterns on the water surface and in the resulting underwater caustics.

AABB Hierarchy Optimized for Rectangular Grid of Primitives

In my box-with-water demo scene, most geometric primitives are concentrated on the water surface. To accelerate ray tracing and photon tracing, I developed an axis-aligned bounding box (AABB) hierarchy tailored to the rectangular grid of triangles forming the water surface.

The first level of the bounding volume hierarchy partitions the water surface uniformly into a \(k*k\) grid, with an AABB constructed for each cell. At each subsequent level of the hierarchy, each cell is further divided into \(k*k\) subcells with corresponding AABBs, until the max level is reached. At the lowest level of the hierarchy, two triangle primitives are constructed for each rectangular subcell.

For the final render of my box-with-water demo scene, I used \(k=12\) and \(3\) levels for the hierarchy. This configuration balances memory usage with intersection test efficiency, resulting in \(2*(12^3)^2\approx 6\) million triangles for the water surface.

Acknowledgement

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Professor Theodore Kim for his invaluable time, guidance, and support throughout this project, especially during an extremely busy semester.