Procedural Planet Generation Project

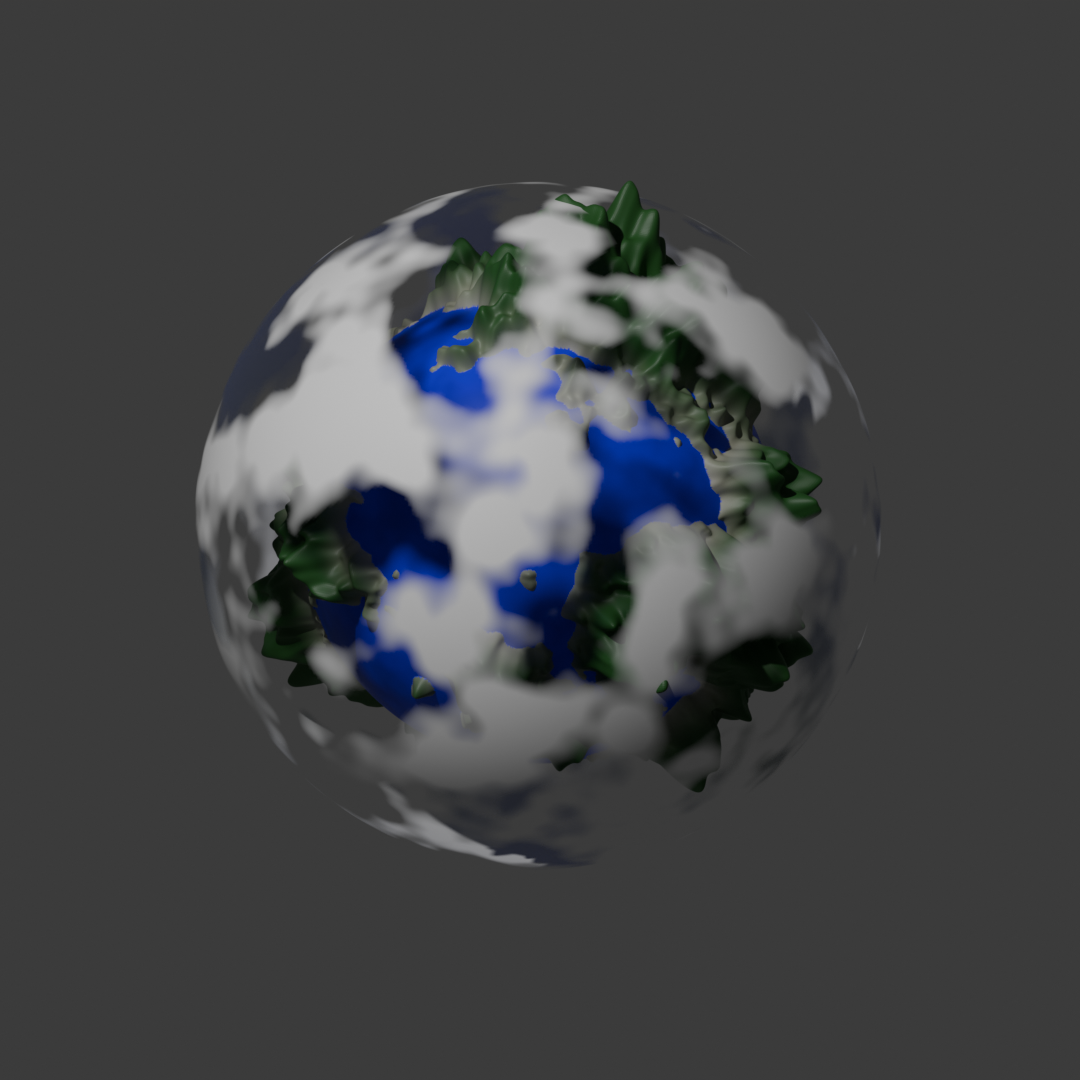

In Spring 2024, I enrolled in Professor Julie Dorsey’s seminar on procedural techniques in computer graphics. Among the topics we explored, I was particularly intrigued by fractal noise, solid texturing, and their applications in generating realistic terrains. Therefore, for part of the course project, I developed procedural algorithms for modeling and texturing celestial bodies – such as rocky planets and gas giants – using the Blender Python API. Following the demo gallery, I will provide an overview of my procedural planet generation algorithm.

Gallery

Noise and Fractal Noise

Noise generation is a fundamental technique that is widely used in computer graphics for procedural generation. One of the most famous noise functions is Perlin noise, introduced by Dr. Ken Perlin in his 1985 paper An Image Synthesizer [1], with several improvements described in his 2002 paper Improving Noise [2]. Another well-known noise function is Worley Noise, also referred to as Voronoi noise, which was introduced by Steven Worley in his 1996 paper A Cellular Texture Basis Function [3].

In the 2004 SIGGRAPH course The Elements of Nature: Interactive and Realistic Techniques, Dr. Kenton Musgrave provided a comprehensive introduction to techniques for leveraging fractal noise to procedurally generate complex natural phenomena, in the section Fractal Terrains and Fractal Planets [4]. In this course, he described how to define a fractal noise using four key factors: the basis function, which is a noise function such as Perlin noise; the fractal dimension, which corresponds with roughness; octaves, which control the level of detail; and lacunarity, which determines the gap between frequencies (typically set to \(2.0\) for doubling the frequency at each octave) [4].

Fractal noise is self-similar at different scales, making it ideal for generating terrains and other natural phenomena. Dr. Musgrave also introduced the terms monofractal, which refers to fractal noise with a uniform fractal dimension everywhere, and multifractal, which has space-varying fractal dimensions and more closely resembles real-world terrains [4]. While I will omit the technical details here, Dr. Musgrave’s work and the techniques discussed in his course have greatly inspired my procedural planet generation algorithm.

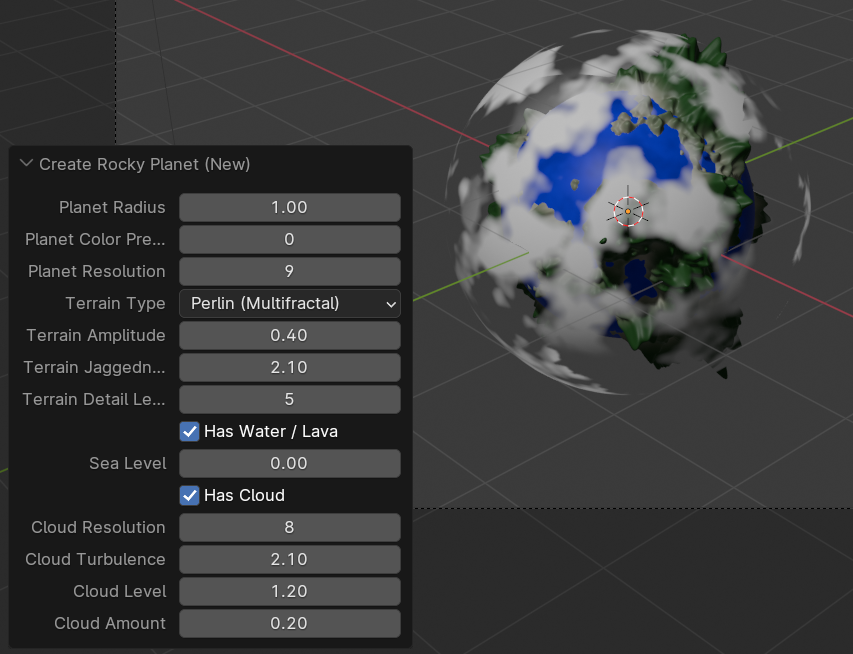

Rocky Planet Generation

Rocky planets are Earth-like planets with solid surfaces and complex terrain shapes. The generation of a rocky planet can be divided into three stages: 1. terrain generation / modeling; 2. terrain texturing; 3. cloud generation.

|

|---|

| Rocky Planet Generation – Blender Plugin Parameters |

Terrain Generation / Modeling

To model the shape of a rocky planet in Blender, each planet starts as an unit icosphere with user-defined subdivision level. The generator supports three types of fractal noise: ridged monofractal Perlin noise, ridged multifractal Perlin noise, and multifractal Perlin noise. Here the “ridged” basis functions are implemented as one minus the absolute value of the original noise, as introduced in Dr. Musgrave’s talk [4]. Ridged fractal noise creates ridge-like features at positions where the original noise value crosses zero, making it highly suitable for generating terrain features such as mountain ranges.

In an earlier version, a combination of Perlin noise and Voronoi noise was used, with Voronoi noise intended to create edges resembling mountain ridges. However, this approach proved less effective than the current implementation.

To generate the terrain geometry, the specified fractal noise basis function is evaluated at each vertex of the icosphere. The noise value determines the radial distance of the vertex from the planet’s center. Users can adjust the fractal noise’s amplitude, frequency, and octaves, which roughly correspond to the terrain’s height, jaggedness, and detail level. If the user specifes that the planet includes liquid features (water / ice / lava), noise values below a user-specified threshold will be clamped to this threshold to represent those features.

Terrain Texturing

There are three texturing and coloring presets for rocky planets:

- Earth-like planets with vegetation and liquid water seas.

- Icy planets with snowy mountains and frozen lakes.

- Fiery planets with volcanoes and lava lakes.

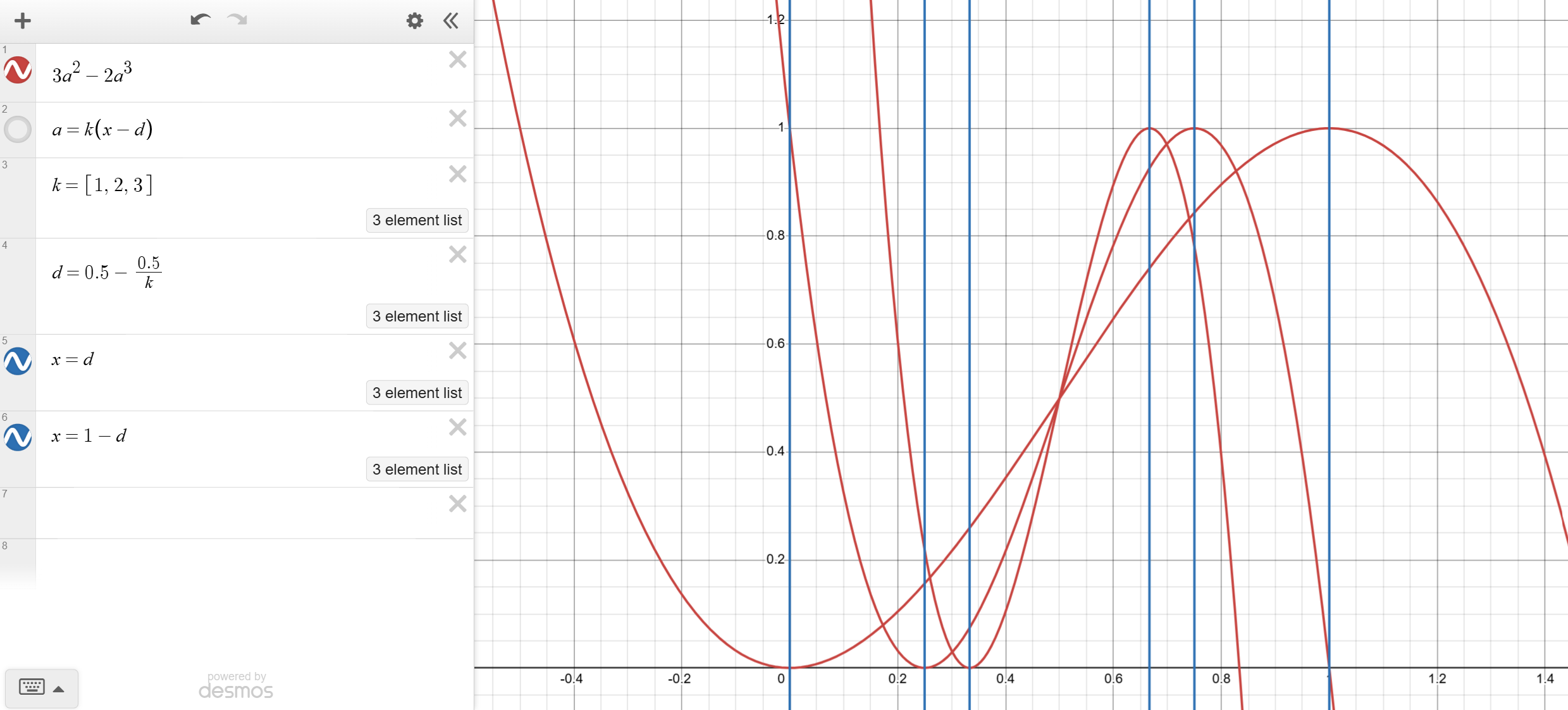

After the user selects a preset, texturing is applied by interpolating four key colors: the min/max land color, and the min/max liquid color. The max land color is achieved at the maximum noise level, while the max liquid color is applied at the liquid threshold. Similarly, the min land color and min liquid color correspond the minimum noise level. If the noise value falls below the liquid threshold, the min/max liquid colors are interpolated using smoothstep interpolation.

If the noise value is higher than the threshold, or if the planet doesn’t have liquid, the min/max land colors are interpolated using a modified smoothstep function with a “steepness” parameter. I created a visualization using Desmos to illustrate the modified smoothstep function I designed:

|

|---|

| Modified Smoothstep with Steepness Parameter |

In the figure, \(k\) is the steepness parameter that controls the overall “slope” of the central part of the interpolation curve. A higher \(k\) results in a steeper curve, with \(k = 1\) equivalent to the original smoothstep function. \(d\) is the “offset”, and for \(x < d\) or \(x > 1-d\), the function value is clamped to \(0\) or \(1\), respectively.

For the procedural texturing process, each color preset uses a different steepness parameter. The steepness controls the clarity of the boundary between the min/max land colors. Additionally, the interpolation coefficient calculated for land is perturbed with a small-scale Perlin noise to introduce more variation in the color distribution across the planet’s surface.

Cloud Generation

Moreover, the user can specify whether the planet has clouds. If enabled, an additional icosphere with user-controlled subdivision level is generated concentrically around the planet, surrounds it at a radius specified by the user.

The appearance of the clouds is created by manipulating the alpha channels of the vertices. Perlin noise is again used to assign a value to each cloud vertex. Vertices with a noise value below a lower threshold are assigned an alpha value of \(0\) (completely transparent), while vertices with a noise value above an upper threshold are assigned an alpha value of \(1\) (completely opaque).

The alpha value is linearly interpolated between the upper and lower thresholds to create a gradual fading effect near the edges of the clouds. Users can adjust the threshold values to control the amount of cloud coverage and modify the noise frequency to alter the “fuzziness” of the clouds. The clouds are colored according to the planet’s selected color preset.

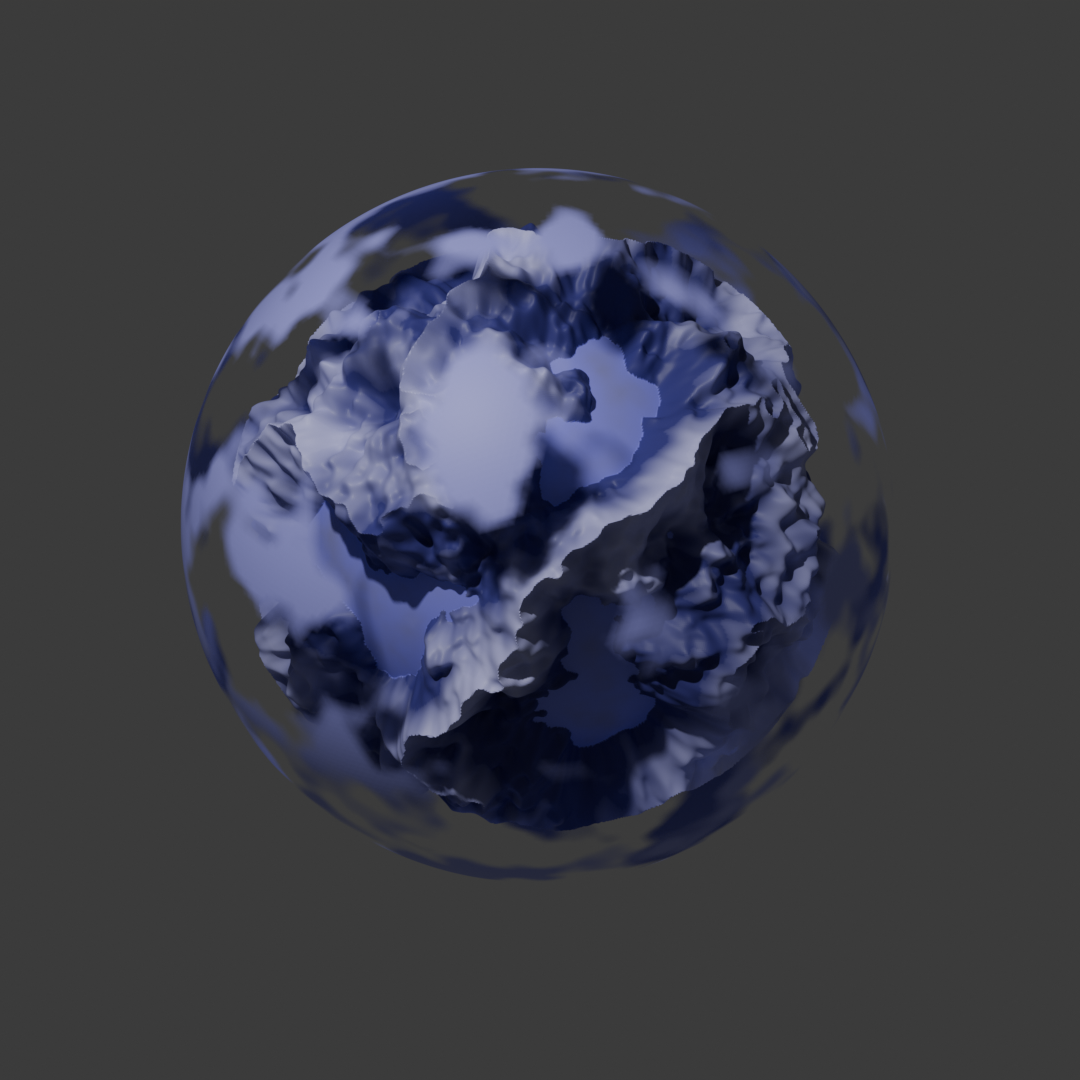

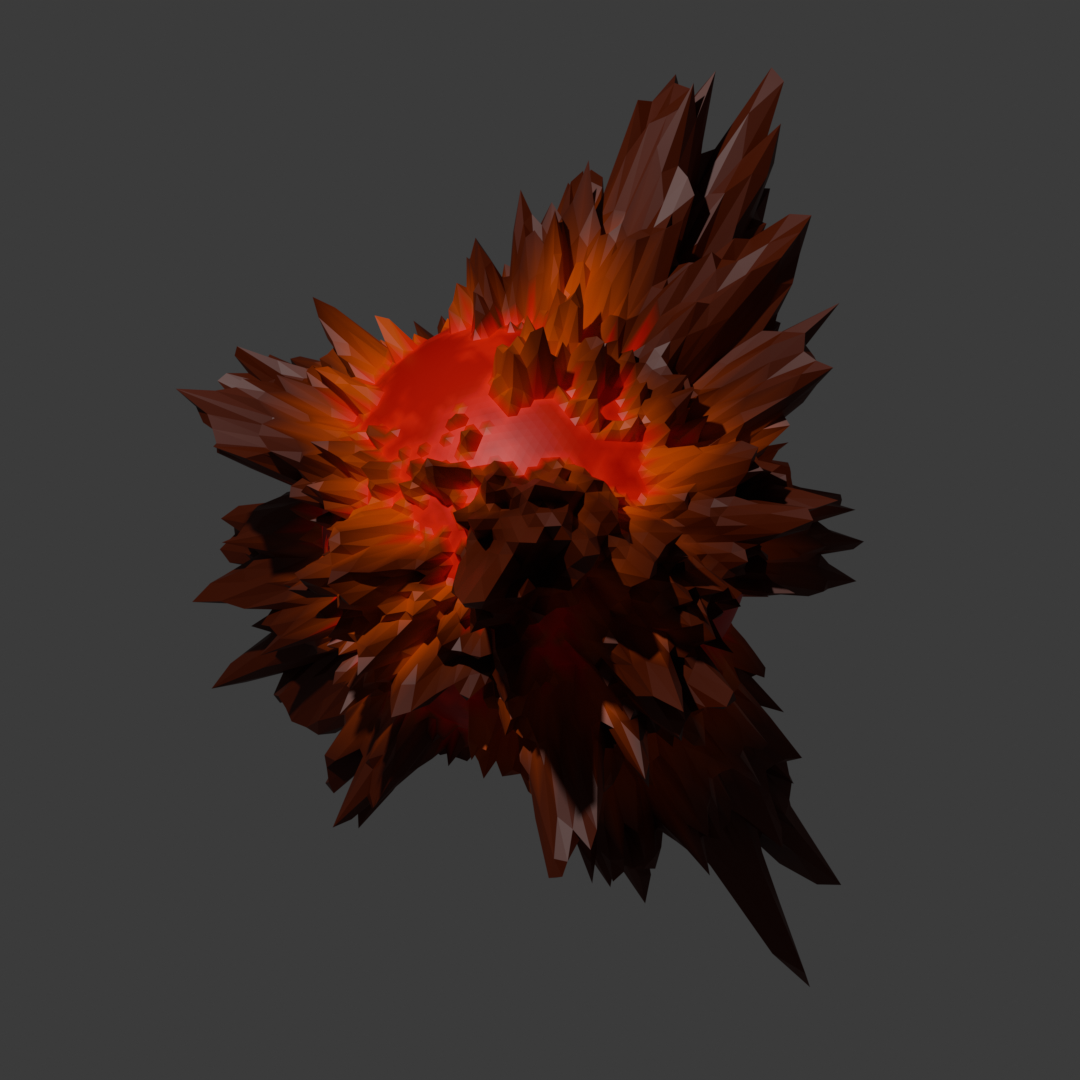

|  |

|---|---|

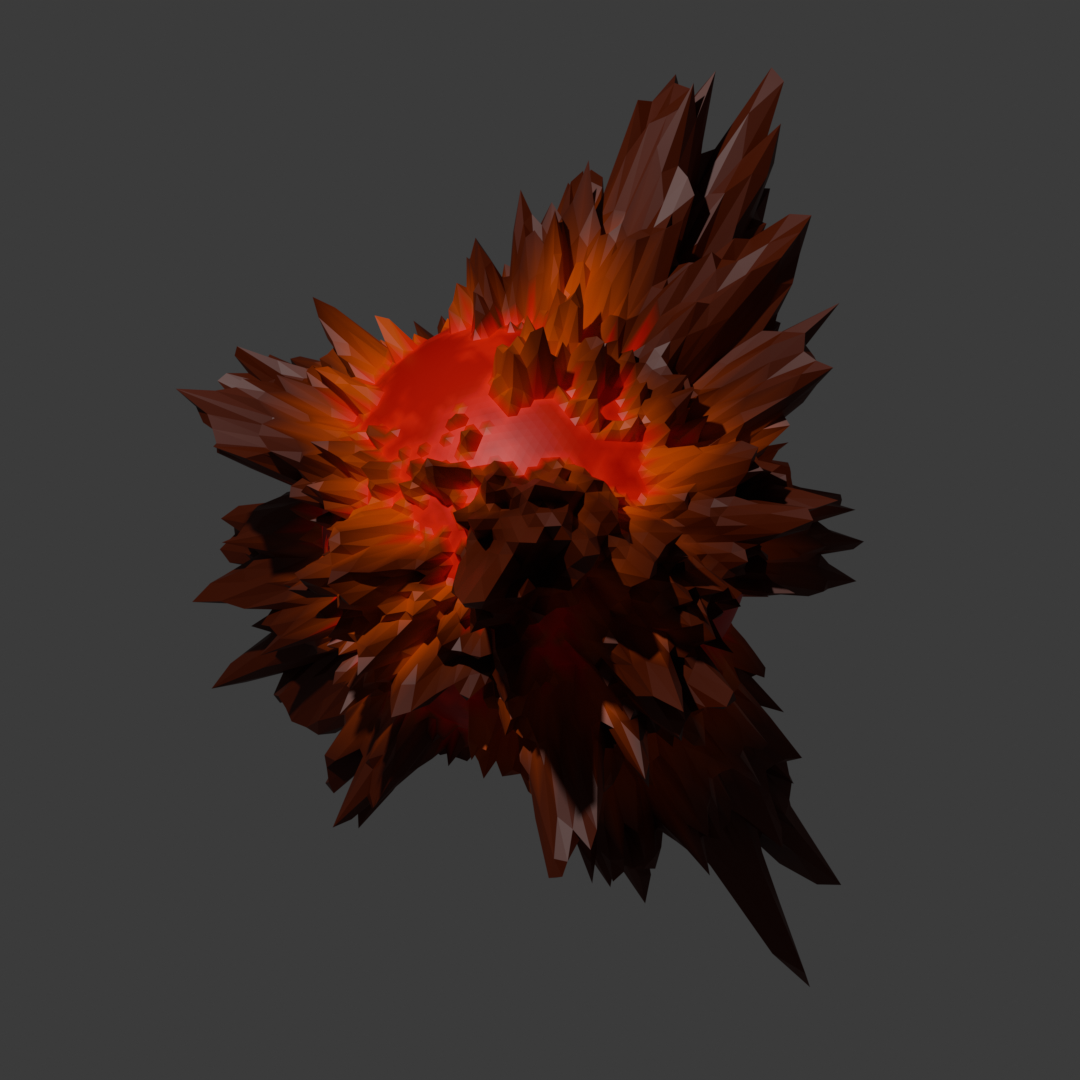

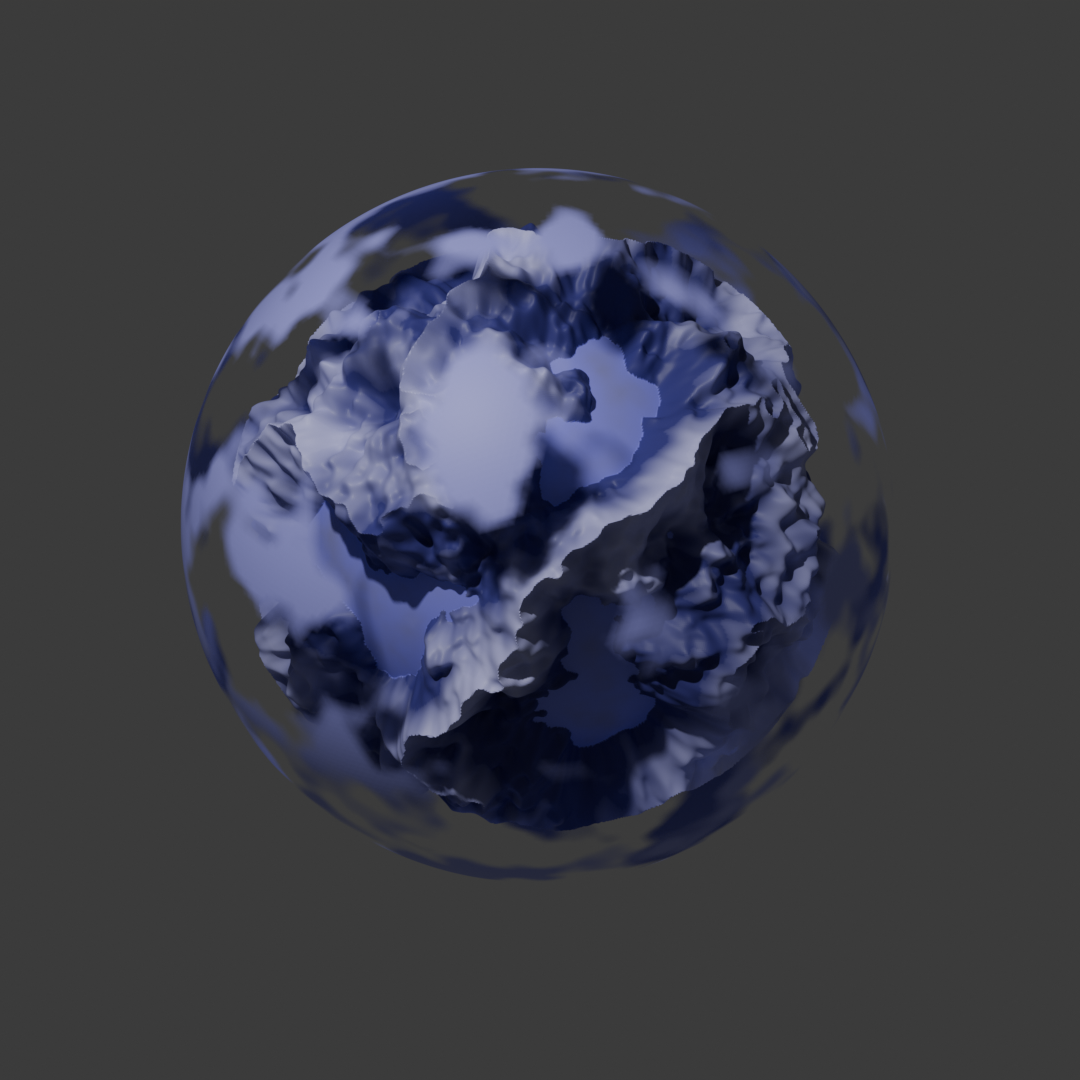

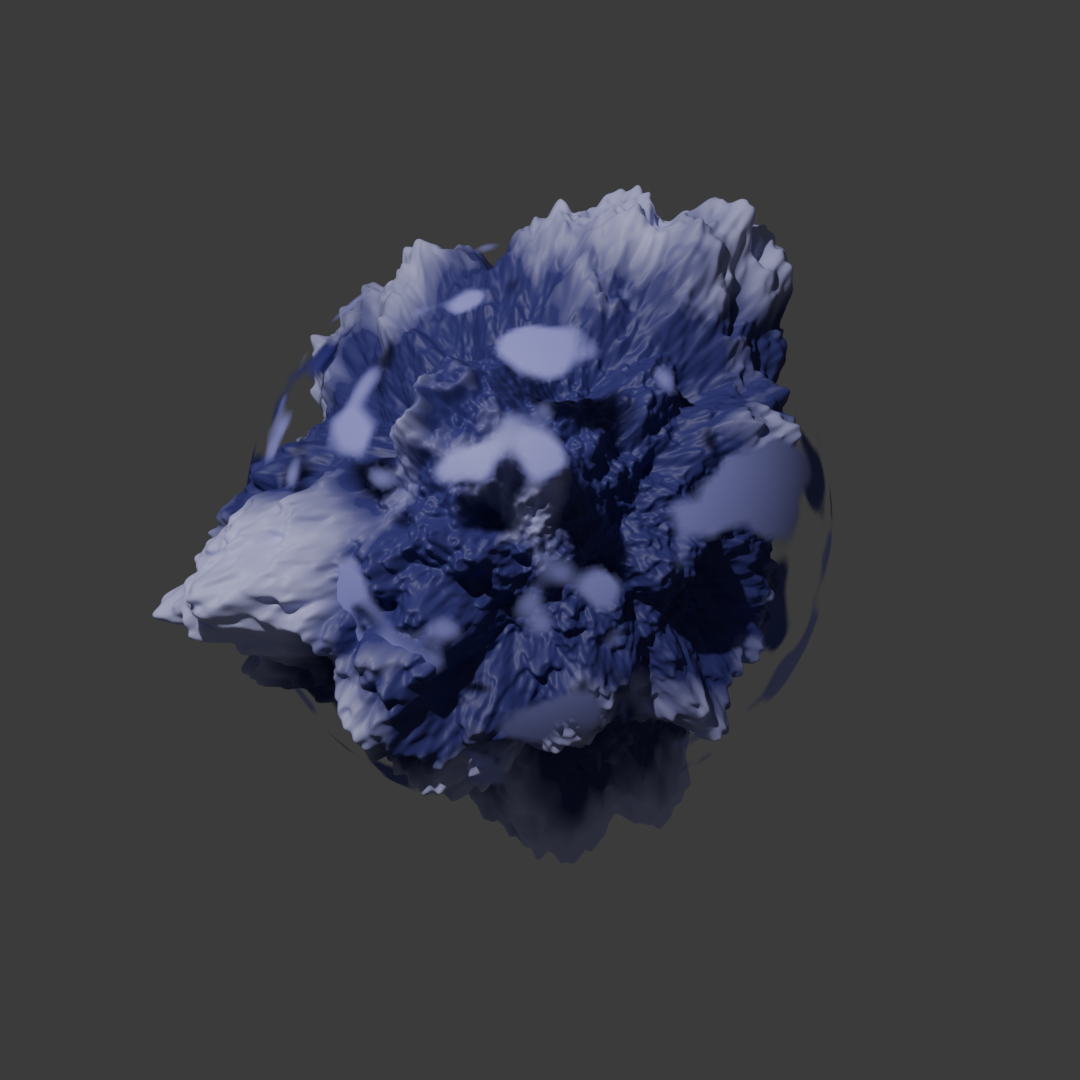

| An Icy Rocky Planet (More Realistic) | A Fiery Rocky Planet (More Imaginary) |

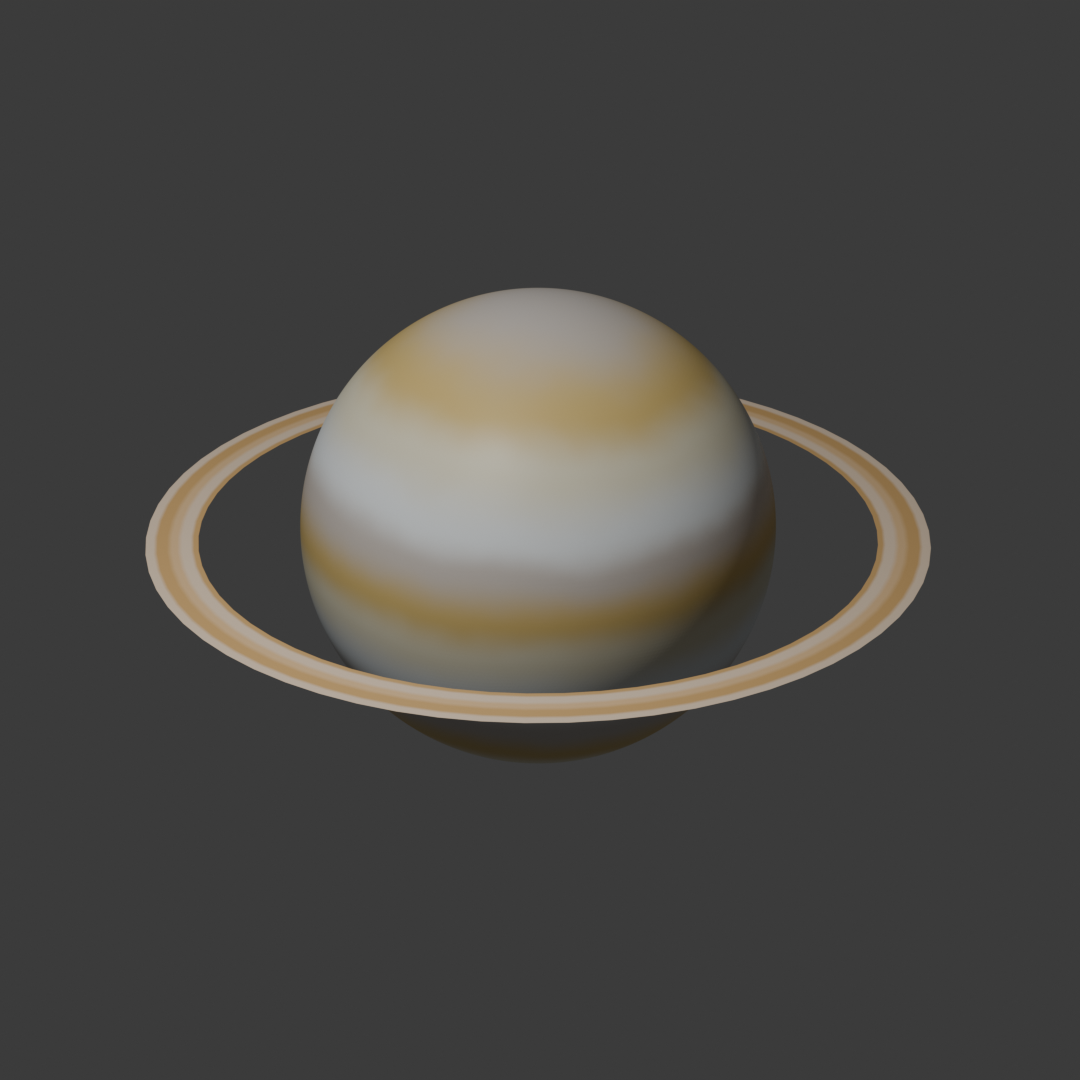

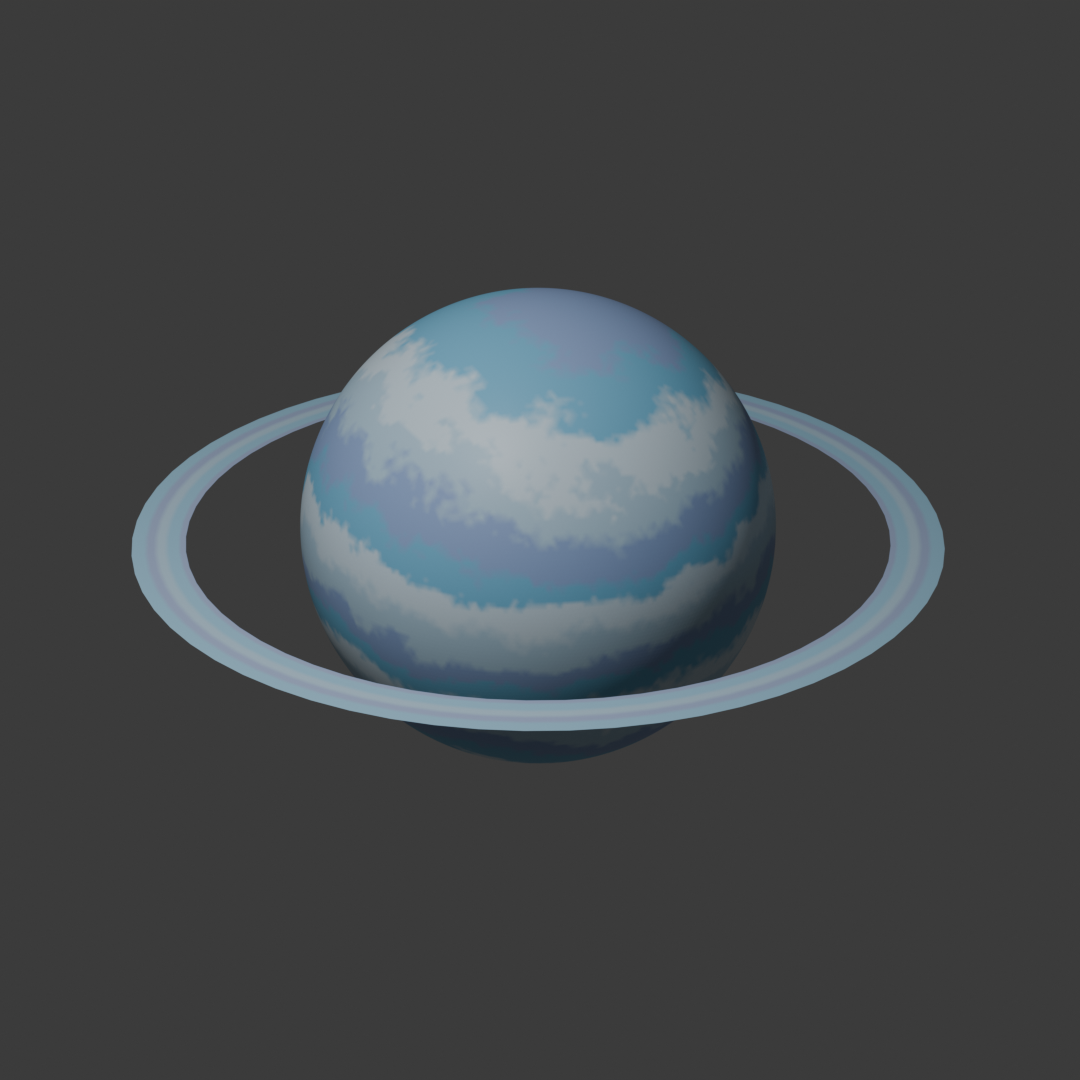

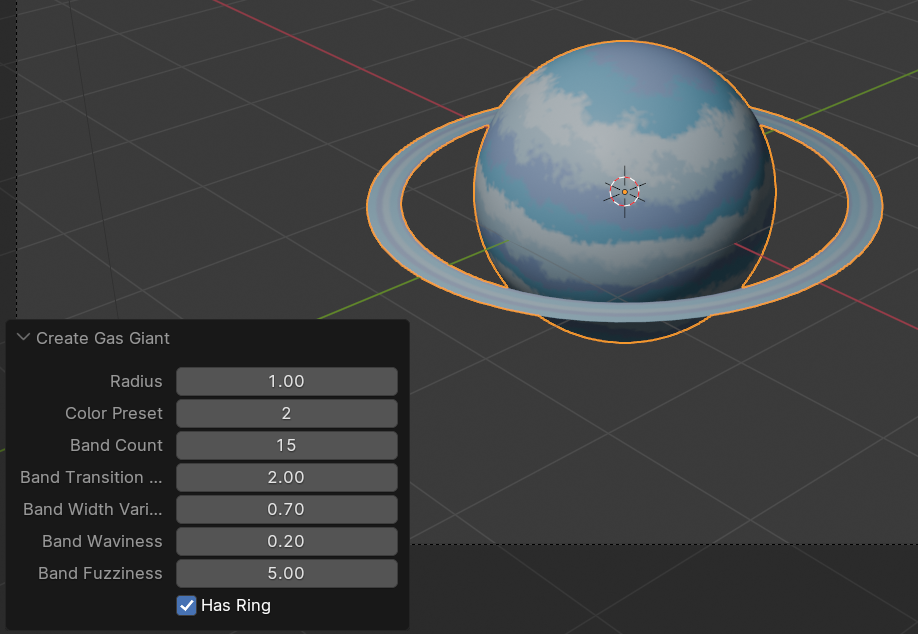

Gas Giants Generation

Gas giants are Jupiter-like planets that lack surfaces with complex terrains. Nonetheless, they typically feature colorful bands at different latitude intervals. Therefore, the key to generating visually appealing gas giants is to procedurally texture the “color bands” of the planets.

|

|---|

| Gas Giant Generation – Blender Plugin Parameters |

Color Bands Generation

Assuming the gas giants are upright with respect to the \(z\)-axis, so the \(z\)-values represents the heights. After users specify the number of color bands, a set of band locations (\(z\)-values) is determined by dividing the height into equal intervals and adding random perturbations to the intermediate band heights, excluding the top (\(z=1\)) and bottom (\(z=-1\)) boundaries. Each calculated height corresponds to a color from one of the two color presets specified by the user: one for gas giants resembling the colors of Jupiter and Saturn, and another for gas giants resembling the colors of Uranus and Neptune.

In each interval between two band heights, colors are calculated by interpolation using the modified smoothstep function, with an adjustable steepness parameter to control the clarity of the band boundaries. However, similar to Dr. Perlin’s “marble” function [1], the \(z\)-coordinate of each vertex is perturbed by a fractal Perlin noise before being used to evaluate the interpolation coefficient. This process creates color bands on the gas giant’s surface, with turbulent features at the boundaries of each color band. Users can also control the intensity of the turbulence and the fuzziness of the boundaries by adjusting the amplitude and frequency of the perturbing noise.

Ring Generation

Users can optionally add a ring (like Saturn’s) to the generated gas giant. The ring is modeled as a flattened torus with inner and outer radii randomized within a certain range. It uses the same color preset as the planet, with color bands on the ring determined by each vertex’s radial distance from the planet’s center.